Stock market today: Wall Street rallies on Election Day as economy remains solid

- By 6122ee467d22433199917c7d

- •

- 05 Nov, 2024

Stock market today: Wall Street rallies on Election Day as economy remains solid

U.S. stocks are rallying Tuesday as voters head to the polls on the last day of the presidential election and as more data piles up showing the economy remains solid.

The S&P 500 was up 1.2% in afternoon trading, rising closer to its record set last month. The Dow Jones Industrial Average was up 431 points, or 1%, as of 12:50 p.m. Eastern time, while the Nasdaq composite was 1.5% higher.

Treasury yields also rallied after a report showed growth for retailers, transportation companies and other businesses in the U.S. services industries accelerated last month. That was despite economists’ expectations for a slowdown, and the Institute for Supply Management said it was the strongest growth since July 2022.

The strong data offered more hope that the U.S. economy will remain solid and avoid a long-feared recession following the worst inflation in generations.

Excitement about the artificial-intelligence boom also helped lift the stock market, as it has for much of the last year. Software company Palantir Technologies jumped 23% after delivering bigger profit and revenue than analysts expected for the latest quarter. It’s an industry known for thinking and talking big, and CEO Alexander Karp said, “We absolutely eviscerated this quarter, driven by unrelenting AI demand that won’t slow down.”

It helped offset a 6.3% drop for NXP Semiconductors. The Dutch company fell to one of the largest losses in the S&P 500 after warning that weakness it saw in the industrial and other markets during the latest quarter is spreading to Europe and the Americas.

The market’s main event, though, is the election, even if the result may not be known for days, weeks or months as officials count all the votes. Such uncertainty could upset markets, along with an upcoming meeting by the Federal Reserve on interest rates later this week. The widespread expectation is for it to cut its main interest rate for a second straight time, as it widens its focus to keeping the job market solid in addition to getting inflation under control.

Despite all the uncertainty heading into the final day of voting, many professional investors suggest keeping the focus on the long term and what corporate profits will do over the next few years and a decade. The broad U.S. stock market has historically tended to rise regardless of which party wins the White House, even if each party’s policies help and hurt different industries’ profits underneath the surface.

Since 1945, the S&P 500 has risen in 73% of the years where a Democrat was president and 70% of the years when a Republican was the nation’s chief executive, according to Sam Stovall, chief investment strategist at CFRA.

The U.S. stock market has tended to rise more in magnitude when Democrats have been president, in part because a loss under George W. Bush’s term hurt the Republican’s average. Bush took over as the dot-com bubble was deflating and exited office when the 2008 global financial crisis and Great Recession were devastating markets.

The S&P 500 ended up rising 69.6% from that Election Day in 2020 through Monday, following President Joe Biden’s win. It set its latest all-time high on Oct. 18, as the U.S. economy bounced back from the COVID-19 pandemic and managed to avoid a recession despite a jump in inflation.

In the prior four years, the S&P 500 rose 57.5% from Election Day 2016 through Election Day 2020, in part because of cuts to tax rates signed by Trump.

Investors have already made moves in anticipation of a win by either Trump or Vice President Kamala Harris. The value of the Mexican peso might fall if Trump’s tariffs on Mexico come to fruition, for example.

But Paul Christopher, head of global investment strategy at Wells Fargo Investment Institute, suggests not getting caught up in the pre-election moves, or even those immediately after the polls close, “which we believe will face inevitable tempering, if not outright reversals, either before or after Inauguration Day.”

In the bond market, the yield on the 10-year Treasury rose to 4.34% following Tuesday morning’s strong report on U.S services businesses from 4.29% late Monday.

In stock markets abroad, indexes were mixed in Europe and Asia. The moves were mostly modest outside of jumps of 2.3% in Shanghai and 2.1% in Hong Kong.

Savannah Britt owes about $27,000 on loans she took out to attend college at Rutgers University, a debt she was hoping to see reduced by President Joe Biden’s student loan forgiveness efforts.

Her payments are currently on hold while courts untangle challenges to the loan forgiveness program. But as the weeks tick down on Biden’s time in office, she could soon face a monthly payment of up to $250.

“With this new administration , the dream is gone. It’s shot,” said Britt, 30, who runs her own communications agency. “I was hopeful before Tuesday. I was waiting out the process. Even my mom has a loan that she took out to support me. She owes about $18,000, and she was in the process of it being forgiven, but it’s at a standstill.”

President-elect Donald Trump

and his fellow Republicans have criticized Biden’s loan forgiveness efforts, and lawsuits by GOP-led states have held up plans for widespread debt cancellation. Trump has not said what he would do on loan forgiveness, leaving millions of borrowers facing uncertainty over their personal finances.

The economy

was an important issue in the election, helping to propel Trump to victory. But for borrowers, concerns about their finances extend beyond inflation to include their student debt, said Persis Yu, managing counsel for the Student Borrower Protection Center.

“That’s a big part of what is making life unaffordable for them is this burden of expenses that they can’t seem to get out from under,” Yu said.

Student loan cancellation was not a focus of the campaign for either Trump or Vice President Kamala Harris , who steered clear of the issue at her political events. The issue came up just once in the September presidential debate, when Trump hammered Harris and Biden for failing to deliver their promise of widespread forgiveness. Trump called it a “total catastrophe” that “taunted young people.”

Biden promised the student loan cancellation program during his run for the presidency. From its launch, Biden’s loan forgiveness faced relentless pushback from opponents who said it heaped advantage on elites and came at the expense of those who repaid their loans or did not attend college.

Biden’s first plan to cancel up to $20,000 for millions of people was blocked by the Supreme Court last year. A second, narrower plan has been halted by a federal judge after Republican-led states sued. A separate policy intended to lower loan payments for struggling borrowers has been paused by a judge, also after Republican-controlled states challenged it.

Overall, Biden’s efforts were relatively unpopular, even among those with student loans. Three in 10 U.S. adults said they approved of how Biden had handled student loan debt, according to a poll this spring from the University of Chicago Harris School of Public Policy and The Associated Press-NORC Center for Public Affairs Research . Four in 10 disapproved. The others were neutral or didn’t know enough to say.

Project 2025, the blueprint for a hard-right turn in American government that aligns with some Trump priorities , calls for getting the federal government out of the student loan business and doing away with repayment plans that pre-date the Biden administration.

Even without directly addressing student loans, Trump has made promises that would affect them. He has pledged to eliminate the U.S. Department of Education, which manages the $1.6 trillion federal student loan portfolio. It’s unclear which entity would take that responsibility if the department were eliminated, which would require approval from Congress.Yu noted the Biden administration managed to cancel student loans for about 5 million borrowers , even though the signature forgiveness effort has been blocked. The administration did it by leaning into loan cancellation programs already in effect. For example, an existing student loan forgiveness program for public service workers has granted relief to more than 1 million Americans, up from just 7,000 who were approved before it was updated by the Biden administration two years ago.

“A lot of the cancellation that we saw in the last couple of years was because the Biden administration was committed to making the programs that are actually enshrined in law work for people,” Yu said.

The challenge of repaying the $23,000 she has borrowed to study education policy at Columbia University weighs on 23-year-old Zaakirah Rahman, but she said she did not see an alternative to pursing an advanced degree.

“It feels like the threshold for things is getting higher and suddenly getting a bachelor’s degree isn’t enough,” she said. “It’s expensive. It’s super expensive. But it seems like you don’t really have a choice.”

Sabrina Calazans, 27, owes about $30,000 on federal student loans from her college days at Arcadia University in Pennsylvania. Her payments also have been on hold, but she could soon face a monthly payment of over $300.

“As a first-generation American, I live at home with my family, I contribute to our household finances, and that payment is a lot for me and so many others like me,” said Calazans, who is originally from Brazil.

In her role as managing director for Student Debt Crisis Center, Calazans said she has been telling people to stay up to date on developments by using the loan simulator on the Federal Student Aid website and reading updated information on forgiveness qualifications and repayment programs.

“There’s a lot of confusion about student loans,” Calazans said, and not just among young people. “We’re seeing a lot of parents take out more debt for their children to be able to go to school. We’re seeing older folks go back to school and having to take out loans as well.”

SOURCE: AP NEWS

Some manufacturers and retailers are urging President Joe Biden to invoke a 1947 law as a way to suspend a strike by 45,000 dockworkers that has shut down 36 U.S. ports from Maine to Texas.

At issue is Section 206 of the Labor Management Relations Act of 1947, better known as the Taft-Hartley Act. The law authorizes a president to seek a court order for an 80-day cooling-off period for companies and unions to try to resolve their differences.

Biden has said, though, that he won’t intervene in the strike.

Taft-Hartley was meant to curb the power of unions

The law was introduced by two Republicans — Sen. Robert Taft of Ohio and Rep. Fred Hartley Jr. of New Jersey — in the aftermath of World War II. It followed a series of strikes in 1945 and 1946 by workers who demanded better pay and working conditions after the privations of wartime.

President Harry Truman opposed Taft-Hartley, but his veto was overridden by Congress.

In addition to authorizing a president to intervene in strikes, the law banned “closed shops,” which require employers to hire only union workers. The ban allowed workers to refuse to join a union.

Taft-Hartley also barred “secondary boycotts,’' thereby making it illegal for unions to pressure neutral companies to stop doing business with an employer that was targeted in a strike.

It also required union leaders to sign affidavits declaring that they did not support the Communist Party.

Presidents can target a strike that may “imperil the national health and safety”

The president can appoint a board of inquiry to review and write a report on the labor dispute — and then direct the attorney general to ask a federal court to suspend a strike by workers or a lockout by management.

If the court issues an injunction, an 80-day cooling-off period would begin. During this period, management and unions must ”make every effort to adjust and settle their differences.’'

Still, the law cannot actually force union members to accept a contract offer.

Presidents have invoked Taft-Hartley 37 times in labor disputes

According to the Congressional Research Service, about half the time that presidents have invoked Section 206 of Taft-Hartley, the parties worked out their differences. But nine times, according to the research service, the workers went ahead with a strike.

President George W. Bush invoked Taft-Hartley in 2002 after 29 West Coast ports locked out members of the International Longshore and Warehouse Union in a standoff. (The two sides ended up reaching a contract.)

Biden has said he won’t use Taft-Hartley to intervene

Despite lobbying by the National Association of Manufacturers and the National Retail Federation, the president has maintained that he has no plans to try to suspend the dockworkers’ strike against ports on the East and Gulf coasts.

On Wednesday, before leaving Joint Base Andrews for an air tour of North Carolina to see the devastation from Hurricane Helene, Biden said the port strike was hampering efforts to provide emergency items for the relief effort.

“This natural disaster is incredibly consequential,” the president said. “The last thing we need on top of that is a man-made disaster — what’s going on at the ports.”

Biden noted that the companies that control East and Gulf coast ports have made huge profits since the pandemic.

“It’s time for them to sit at the table and get this strike done,” he said.

Though many ports are publicly owned, private companies often run operations that load and unload cargo.

William Brucher, a labor relations expert at Rutgers University, notes that Taft-Hartley injunctions are “widely despised, if not universally despised, by labor unions in the United States.”

And Vice President Kamala Harris is relying on support from organized labor in her presidential campaign against Donald Trump.

If the longshoremen’s strike drags on long enough and causes shortages that antagonize American consumers, pressure could grow on Biden to change course and intervene. But experts like Brucher suggest that most voters have already made up their minds and that the election outcome is “really more about turnout” now.

Which means, Brucher said, that “Democrats really can’t afford to alienate organized labor.”

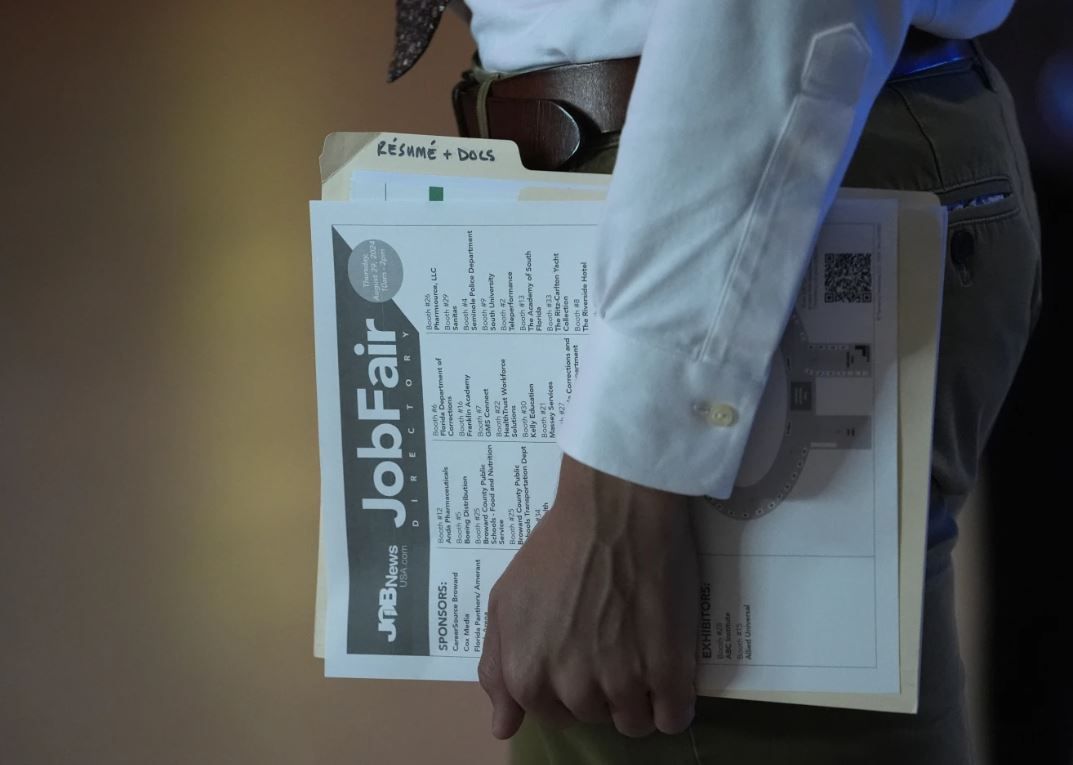

Laid off by the music streaming service Spotify last year, Joovay Arias figured he’d land another job as a software engineer fairly soon. His previous job search, in 2019, had been a breeze.

“Back then,” he said, “I had tons of recruiters reaching out to me — to the point where I had to turn them down.”

Arias did find another job recently, but only after an unexpected ordeal.

“I thought it was going to be something like three months,’’ said Arias, 39. “It turned into a year and three months.’’

As Arias and other jobseekers can attest, the American labor market, red-hot for the past few years, has cooled. The job market is now in an unusual place: Jobholders are mostly secure, with layoffs low, historically speaking. Yet the pace of hiring has slowed, and landing a job has become harder. On Friday, the government will report on whether hiring slowed sharply again in August after a much-weaker-than-expected July job gain.

“If you have a job and you’re happy with that job and you want to hold onto that job, things are pretty good right now,” said Nick Bunker, economic research director for North America at the Indeed Hiring Lab. “But if you’re out of work or you have a job and you want to switch to a new one, things aren’t as rosy as they were a couple of years ago.’’

Since peaking in March 2022 as the economy accelerated out of the pandemic recession, the number of listed job openings has dropped by more than a third, according to the government’s latest monthly report on openings and hiring .

Temporary-help firms have reduced jobs for 26 of the past 28 months. That’s a telling sign: Economists generally regard temp jobs as a harbinger for where the job market is headed because many employers hire temps before committing to full-time hires.

In a roundup this week of local economic conditions , the Federal Reserve’s regional banks reported signs of a decelerating job market. Staffing agencies have said that job gains have slowed “as firms are approaching hiring decisions with greater hesitancy,” the New York Fed found. “Job candidates are lingering on the market longer.”

The Minneapolis Fed said that a staffing agency reported that “businesses are getting a lot more picky” about whom they hire. And the Atlanta Fed found that “only a few” companies planned to step up hiring.

Job-hopping, so rampant two years ago, has slowed as workers have gradually lost confidence in their ability to find better pay or working conditions somewhere else. Just 3.3 million Americans quit their jobs in July, compared with a peak of 4.5 million in April 2022.

“People are staying put because they’re afraid they won’t find new jobs,’’ said Aaron Terrazas, chief economist at the employment website Glassdoor.

And the Labor Department has reported, in its annual revised estimates of employment growth, that the economy added 818,000 fewer jobs in the 12 months that ended in March than it had previously estimated.

In one respect, it’s not at all surprising that the pace of hiring is now moderating. Job growth in 2021 and 2022, as the economy roared back from the COVID-19 recession, was the most explosive on record. Workers gained leverage they hadn’t enjoyed in decades. Companies scrambled to hire fast enough to keep up with surging sales. Many employers had to jack up pay and offer bonuses to keep employees.

It was inevitable — and even healthy, economists say, in the long run — for hiring to slow, thereby easing pressure on wage growth and inflation pressures. Otherwise, the economy could have overheated and forced the Fed to tighten credit so aggressively as to cause a recession.

The post-pandemic jobs boom was a marked contrast to the sluggish recovery from the Great Recession of 2007-2009. Back then, it took more than six years for the economy to recover the jobs that had been lost. By contrast, the breathtaking pandemic job losses of 2020 — 22 million — were reversed in less than 2 1/2 years.

Still, the surging economy ignited inflation, leading the Fed to raise interest rates 11 times in 2022 and 2023 to try to cool the job market and slow inflation. And for a while, the economy and the job market appeared immune from higher borrowing costs. Consumers kept spending, businesses kept expanding and the economy kept growing.

But eventually the continued high rates began leaving their mark. Several high-profile companies, including tech giants like Spotify, announced layoffs last year in the face high interest rates. Outside of the economy’s technology sector, though, and, to a lesser extent, finance, most American companies haven’t cut jobs. The number of people filing first-time applications for unemployment benefits is barely above where it was before the pandemic struck.

Yet the same companies that are keeping workers aren’t necessarily adding more.

“Compared to a year or two ago, it’s a lot more difficult, particularly for entry-level folks,’’ Glassdoor’s Terrazas said. “Because of the gradual drip of layoffs in tech and finance, in professional services over the past year and a half, there have been a lot of high-skilled, experienced folks on the job market.

“By all evidence, they are finding jobs. But they are also pushing more entry-level folks further and further down the queue… Recent grads, folks without a lot of on-the-job experience are feeling the effects of suddenly competing with people who have two, five, 10 years’ experience in the jobs market. When those big fish are in the market, the little fish naturally get squeezed out.’’

Despite the pressure of the highest interest rates in decades, the economy remains in solid shape, having grown at a healthy 3% annual pace from April through June. Most Americans are enjoying solid job security.

Still, given the growing difficulty of changing jobs, even some of those job holders are feeling the chill.

“The reality is a lot of people, even when they have jobs, are feeling a lot of angst about the economy,’’ Terrazas said. “People are feeling a little bit job insecurity, a lot more pressure in the workplace than they have in a while.’’

In an August survey, the New York Fed found that Americans as a whole are more worried about losing their jobs now than at any time since 2014, when people were just beginning to feel the full effects of the recovery from the Great Recession of 2008-2009.

Adding to the anxiety is that memories of the recent job boom are still fresh.

“The reference point for most people is still 2021, 2022, when the job market was very strong, and what looks like for us economists as a normalization (of the job market from unsustainable levels), I think for a lot of people feels like a loss of status,’’ Terrazas said.

Consider Abby Neff, who, since graduating from Ohio University in May 2023, has struggled to find the “old-fashioned writing job’’ that she hoped to land in journalism

“It’s been pretty tough,” she said, “to find a permanent journalism job.”

In the meantime, Neff, 23, has joined the government’s AmeriCorps agency, which mobilizes Americans to perform community service, in southeastern Ohio. The job doesn’t pay much. But it has given her the opportunity to write and to learn about everything from forestry to sustainable agriculture to watershed management.

She hadn’t expected to encounter such difficulty in finding a job in her field.

“I feel like I did all the ‘right things’ in college,’’ Neff said ruefully.

She edited a campus magazine and made contacts in the business. She has landed some interviews, only to learn later that the job was filled without her having heard from the employer.

“I will get ‘ghosted,’ ‘’ she said. “I almost feel like I have to hunt employers down to even get a response to an application or submission.”

Arias, the software engineer, started looking for a job “the minute I got laid off’’ in June 2023. At first, he was casual about it. He took time off to care for his newborn daughter and drew money out of his severance package from Spotify. But when the job hunt proved difficult, he “decided to really ramp it up’’ early this year.

Arias started driving for a ride-sharing service and getting job leads from passengers. He reached out to a company through which he had taken part in a computer coding bootcamp, seeking contacts. Eventually, the networking paid off with a new job.

Yet the process proved much more frustrating than he had envisioned. Employers he had communicated with would vanish without explanation.

“That’s the worst part about the experience,’’ Arias said. “You get that introductory message. Then you send your resume. And then that’s it. Communication would end there. Or you’d get an automated response. So you don’t know what happened, what you did wrong … It just feels really demoralizing, really stressful, because you don’t know what happened.”